Revolutionary, AC-powered single-motor centrifuge design helps manufacturers filter process fluids automatically

A customer's call of exasperation last spring to Jeffery Beattey confirmed that his recent invention of a new centrifuge for fluid filtration was just in time. "This customer, who has a steel processing plant, said, ‘I'm tired of our centrifugal separator breaking down, I don't care whose separator you give me; just find a better one. I need it for my process. It saved me a million dollars in capital expense, and several hundred thousand dollars per year in operating expense – we can't afford be down'," noted Beattey, president of Midwest Engineered Products Corporation, an original equipment manufacturer based in Indianapolis, Indiana.

What Midwest showed the processor was an all-new centrifuge that combines a revolutionary bowl/blade clutch design with a single AC motor and AC motor drive; the centrifuge can remove sub-micron-to-one-half-inch particles and fines from virtually any coolant or lubricant at a processing rate ranging from 25 - 135 gpm (gallons per minute).

Called CentraSep, the centrifuge design appears deceptively simple; but it is more effective than all previous designs -- able to remove as much as four times the quantity of fines traditional centrifuges can filter out, and able to extend the fluid life for any given process by at least four times.

Traditional begs for reinvention

"Market necessity is the mother of this invention," according to James Beattey, who founded Midwest in 1981. Through years of calling on all kinds of processing operations and selling them the company's filters, proprietary ScaleBuster de-scaler and Water Ringer evaporator (for oily wastewater from compressor applications), "an opportunity became clear," he said. "We realized that most of the centrifuges sold to get metal fines out of grinding swarf, coolants, phosphate baths, wastewater, and other process fluids, were broken down or abandoned in the corners and bone yards of plants."

Centrifuges usually are installed on a side stream or kidney loop treating a specific manufacturing process. Traditional centrifuge designs, unchanged in 15 years, are notoriously unreliable, resulting in tremendous downtime and operator attention for maintenance, and bearing replacement. Typical units are extremely complicated mechanically and include two motors, one to operate the bowl (rotor) and a second gear motor to perform the scraping for solids discharge, pneumatic clutches, one-inch chains and sprockets, or pinion gears, connecting the motors and loads.

High-speed revolution of the centrifuge's bowl, required to separate and "pack" solid particles against the bowl wall, is brutal on rotor bearings. When bearings fail, it typically takes four-to-six hours to pull the rotor, just so maintenance personnel can begin to access the bearings. "And that's on automatic units," said Jeff Beattey. Mechanical centrifuges also require additional maintenance and service. Every time the bowl is full, the solids need to be removed manually, before the next processing cycle can begin.

To avoid downtime, many processors have given up on centrifuges due to mechanical complexity and reliability issues and have turned to paper filtration systems, sludge tanks and disposal, at a higher operating cost. This is especially true when processors use a critical filtration process - such as grinders, paint booth water, or a plating operation - that runs 24 hours 7-days per week. Costs associated with downtime outweigh the higher operating cost consideration.

A quantum leap

The vision and technology combined in Midwest's new centrifuge reverses and removes virtually all of this downside labor, material and production/performance costs. The centrifuge is completely automatic and, once set up, "can operate out of sight and out of mind, while providing literally unprecedented fluid filtration-performance and product production benefits, in addition to saving huge operating costs," Beattey said. That payback lies in understanding the machine.

Series of firsts

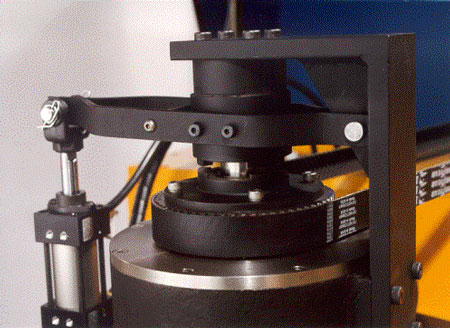

Mechanically, Midwest's centrifuge positively synchronizes, for the first time, the bowl and blade assembly (which consists of two scraper blades and two stilling vanes). A unique positive locking clutch (see diagram) couples the bowl's main spindle and the blade together so that both rotate at precisely the same speed when processing fluids. The motor is linked to the main spindle via a single chevron-style "timing" belt and pulley design that prevents any slippage.

"The fluid is forced to move smoothly throughout the bowl as it strikes an accelerator on entry and descends," noted Beattey. "Physically, that even ‘quiet' flow maximizes the law of centrifugal force: any particles heavier than the liquid are thrown outward and packed against the bowl wall."

Such synchronized rotation also prevents any oscillation of the blade, maximizing separation efficiency and minimizing bearing wear. Oscillation, he said, " is what you want to prevent, as it creates a washout of solids from the bowl, particularly superfines." Because the bowl is a thick centrifugally cast stainless-steel precision-machined part, vibration is dampened further enhancing bearing life.

When the automatic process cycle is complete, the feed pump turns off, the locking clutch uncouples the blade assembly from the main rotor spindle and locks the blades into a fixed position. The bowl is then rotated and the dry, dense particulate that is scraped loose by the blades falls into a collection drum, ready for recycling.

Secret is the electrics

With patents pending on the unique clutch and scraper design, Midwest credits new electrical control "for making the CentraSep a reality," Beattey said. "In this design, the electrical and mechanical components are fused and inseparable."

Midwest realized early on that getting optimum benefits from the clutch design "meant, by definition, using a single motor and single motor controller - but we didn't know if that was possible," said Beattey. Accelerating the bowl and blade very rapidly for the processing cycle, bringing the loaded bowl to a controlled stop, and turning the bowl against the scraper blades, require high, breakaway torque and extremely precise motor control.

After trying several different controls and motor drives in designing the electrical panel for the centrifuge, a local distributor of ABB Automation, Drives & Power Products drives, Scherer Industrial Group, Inc., provided an ACS 600, 10 HP drive. Built into the drive is ABB's unique open-loop Direct Torque Control (DTC) feature, which enables ACS 600 drives to calculate the state (torque and flux) of a motor 40,000 times per second.

According to ABB, this responsiveness to the motor load not only makes the drives virtually tripless – but the absence of any required encoder for feedback from motor to drive also reduces capital costs for the controller by up to 25%, when compared to like flux vector or PWM (Pulse-Width-Modulated) drives.

"Without this brand new drive technology, a single-motor centrifuge would not be a reality," Beattey said.

"Because this open-loop control of torque is so precise, the drives can adapt to and handle changes in load, over-voltages, and even short circuits, immediately," said John Emmert, the electrical designer who helped Midwest with the panel, motor and drive design. This ability to anticipate what the motor is capable of based on its load provides a significant benefit to centrifuge users, Emmert noted. If the load in the bowl, for example, would be too heavy, the AC motor would enter a stall mode, rather than turning the bowl and breaking the shaft or blade assembly. Unlike competitors' products that use gear motors which often break shafts and scraper blade assemblies under those loads, "the electrics anticipate and prevent such an occurrence," Emmert noted.

Both Emmert and Jeff Beattey worked with ABB engineers closely, to develop the proprietary software that Midwest needed to program and operate the drive at extended torque parameters. "We've had no drive failures from a single production unit," noted Beattey, "and with ABB's Mean Time Between Failure (MTBF) on this drive at 150,000 hours and counting, we have a lot of confidence in these critical electrical controls." To ensure that the exact same start-up software is programmed into every drive on all production units, Midwest uses ABB's DriveWindow tool. The Windows-based tool, Beattey said, allows the company to back-up the programming, then restore it on each subsequent drive. "It removes the possibility of operator error," he noted.

This critical programming is not application specific. Instead, to adjust the speed - and centrifugal force - of the bowl for different types of process fluids, Midwest uses a call-out on a PLC built into the panel. The drive, in tandem with the PLC, gives Midwest the flexibility to customize the centrifuge for any kind of application. "This unique drive and motor control capability, which creates up to 2,012 gravitational forces inside the centrifuge and delivers the low-end torque to scrape, literally saved the need for incorporating a second motor into our design," Beattey said.

Reducing waste; improving products

In addition to helping processors in the paint, metal working, grinding, phosphate, glass, heat treat, wastewater and other markets eliminate 80-100% of their usage and costs of paper media filters, the high efficiency of the CentrSep also increases the quality of the solid waste it captures. In a copper wire-drawing application, the "mud" the centrifuge now filters out is 86 percent pure copper and can be reclaimed, since it contains no paper media.

Such effective removal of particulate also can reduce the frequency of cleaning out sludge tanks by 75% (once a year rather than four times a year) or better. "An aluminum wire-drawing plant that now uses this centrifuge had to pay $60,000 every time they dumped a tank; effective filtration eliminated sludge build-up," noted Steve Kappen, centrifuge account executive for Midwest. "Or, for a plating or painting operation that is dipping parts, capturing this particulate minimizes solids build-up inside the tank so that the maximum number of parts can be coated."

Most importantly, the ability to maintain particulate-free process fluids year-in-year-out reduces friction between tools and work surfaces so that the quality of parts produced is higher. "This centrifuge is at 8,000 hours and counting in a zinc-removal application, one of the toughest possible," Beattey said. "And it's removing aluminum fines in a wire-drawing application where the oil is as viscous as 4,000 SSU. The filtering prevents problems, such as die impaction or streaking on the wire."

Midwest noted such filtration capabilities also will play a more critical role in helping processors meet their zero-discharge commitments. "Strategically, you capture the maximum quantity of any contamination at the point of origin," said Kappen. "It's smart business; you improve and extend the life of the process fluids; you pack the particulate as tightly as possible – and you minimize any discharge of this captured particulate into the waste treatment stream."

Built for a lifetime

The in-line performance of the first CentraSep units in a host of very difficult applications have only reinforced Midwest's decision to offer a lifetime guarantee with the centrifuge. Through the warranty, Midwest exchanges, on an annual basis, the entire rotor assembly – all mechanical parts except the motor.

"It's a win-win," according to James Beattey. "Our commitment to customers is long-term. We know they want clean fluids, and we know this product can provide that. It's why we were so deliberate in choosing the word ‘revolutionary' to describe this original design."

The ability to change-out the rotor assembly in record time also keeps filtration lines moving in customer's plants without a hitch. "It's eight bolts, the timing belt and air-line quick connects; the rotor exchange has been done in as little as three minutes and six seconds," said Kappen.

Given the early receptivity to the OEM's re-invention of this product, what's next? "There are other new product ideas on our list waiting for our attention," said Jeff Beattey, "but we already know that increasing the capacity of this centrifuge line is a priority." Adding units that are able to process fluids from 150-225 gpm "is in our future," he noted. Sales prospects of the existing units are bright, too, he said, with Midwest predicting an increase of "several hundred percentage points per year over the next five years," for the CentraSep.

Carl Tuch is the regional manager for ABB Automation, Drives & Power Products.